In the last two decades, India has focused immensely on ramping up capabilities in the manufacturing sector. Government initiatives such as Make in India, Production Linked Incentives (PLI), and improved capabilities in infrastructure such as ports and highways have complimented the country’s manufacturing outlook. Among enterprises and even MSMEs, a renewed interest in enhancing manufacturing capabilities has also favoured this positive outlook.

Currently, manufacturing contributes more than 17% to GDP and employs just over 27 million people. India aspires to improve manufacturing contribution to 25%, which evidently is crucial to the ambitions of a $5 trillion economy. Transformation in manufacturing has so far helped define India’s economic trajectory but sustaining this movement will be crucial. There are several means to sustain the manufacturing agenda, but two factors stand out finding a competitive edge and focusing on skills.

THE DISCOVERY OF A MOAT

With the discourse on global outlook not very optimistic, the only recourse to organisations engaged in manufacturing and export-linked sectors is to find a moat that helps sustain. Today’s geopolitical discourse which involves the vagaries of tariffs implies that what worked in the pre-pandemic era is no longer relevant to organisations. Challenges such as high energy costs, inconsistent regulatory frameworks, and trade barriers are likely to have a lasting impact on organisations that are keen on engaging in global trade (export-import). Additionally, newer technologies such as automation and generative-AI have pushed organisations to relook newer ways to achieve objectives of supply-chain and bottom-line.

With such a fragmented geopolitical discourse, India which aims to export goods worth $1 trillion by 2030, may have to reposition itself as more than just a major global manufacturing hub. Individual organisations may have to not only augment domestic capacity and their strategic investments but also find a strong moat. A moat that is limited to not just price based differentiation but also the quality of products when it comes to manufacturing.

For example, if an average customer perceives a “Made-in-China” product as a “cheap alternative”, an Indian manufacturer may provide better value by simply not competing on the price front. Some non-price related USP could not only differentiate the Indian offering but also could help pass on a convincing message to the international community.

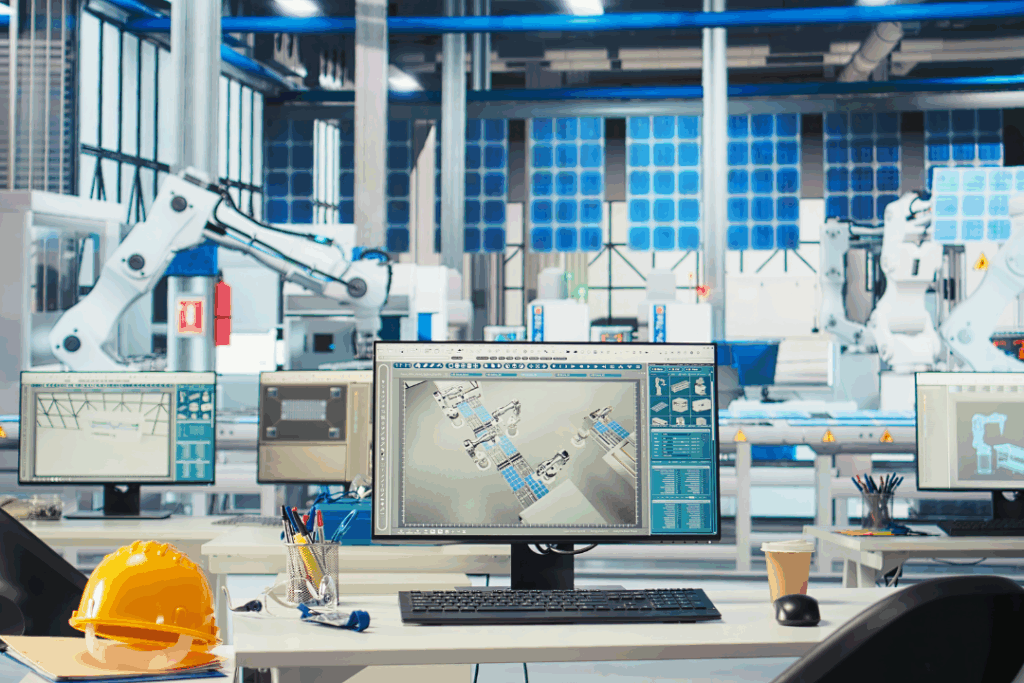

While finding a business moat is intrinsic and unique to an individual manufacturing organisation, the greater industry focus is a broader set of themes to focus on. These themes or the future of manufacturing in India will be shaped by newer skills and capabilities such as automation, robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and data-driven processes.

Colloquially also referred to as Industry 4.0, this umbrella integrates smart technology to turn manufacturing into an efficient and precise workhorse. India is already witnessing some level of efficiency here with organisations such as Tata Motors, Mahindra, and Maruti Suzuki deploying AI-powered capabilities to reduce defects or enhance productivity. In addition to automotive, many sectors such as pharmaceuticals, heavy engineering, telecom, and even custom-manufacturers have deployed industry 4.0 practices.

Leading industry researchers estimate that industry 4.0 tenets can boost efficiency by 20-30% helping Indian manufacturers compete globally. But a widespread adoption of these technologies so far has shown challenges – high capital investment and shortage of skilled labour. According to a report by the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC), India already needs over 30 million skilled workers in the manufacturing sector by 2030. While government initiatives such as Skill India can bridge the “skills gap”, the need for skills for industry 4.0 will be persistently felt unless there is a collaborative approach between the government and industry.

So far, India has had a good run with the numerous policy initiatives, and the on-ground change from the manufacturers and consumers themselves. But India has the potential to achieve more than 25% of its GDP from manufacturing. In fact, economic forecasts and analyses from CII estimates that the manufacturing sector’s share in the GVA has a potential to rise from the current 17% to over 25% by 2030-31, and to 27% by 2047-48. That, only if sustained efforts to boost domestic manufacturing capabilities and domestic value addition continues.

So, the India manufacturing story has a lot more to offer than just opportunities or comparisons with other countries (China, Vietnam, Japan, Britain, Germany, etc). But to do that, Indian enterprises will have to chalk out on a workable navigation strategy. Collaboration and focusing on innovation can help India set course towards a new future – one where the country drives the standards in manufacturing.