Logic Fruit Technologies is one of the companies contributing to India’s self-reliant electronics journey. Based in Gurugram, the engineering-led company started as a high-speed interface specialist and is now expanding into full-stack development of single-board computers (SBCs) for mission-specific applications. Known for its work in PCIe, ARINC 818, and FPGA-based systems, Logic Fruit has recently developed a new line of indigenously built SBCs in collaboration with DRDO, aimed at supporting rugged, industrial-grade computing needs.

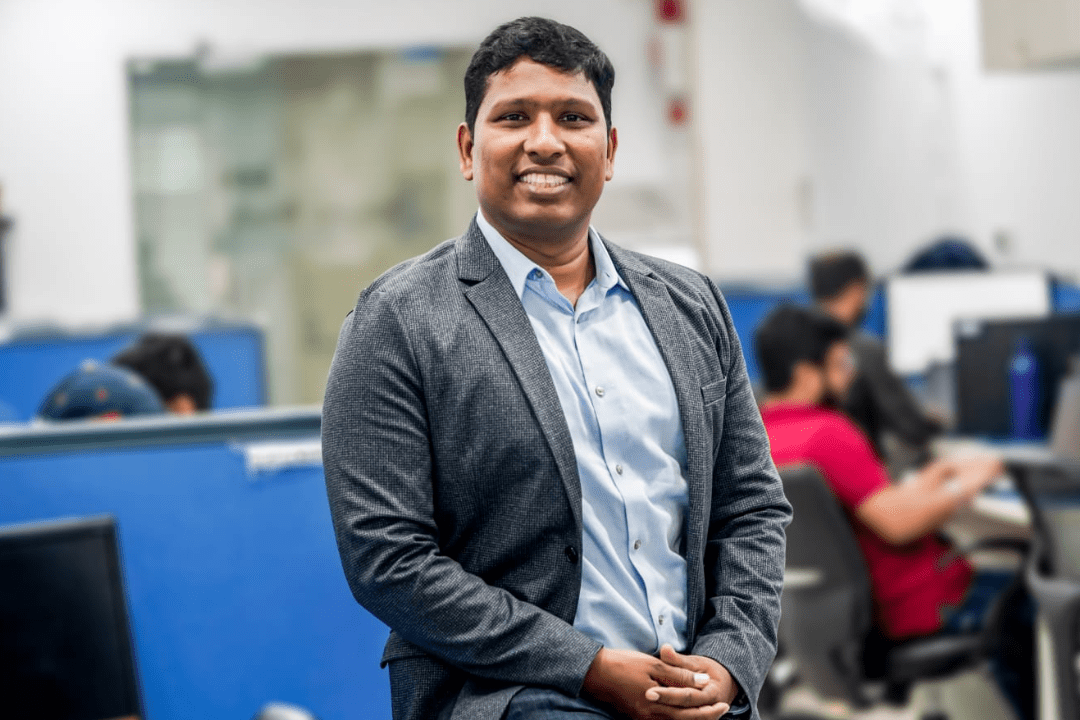

Sanjeev Kumar, Co-Founder and CEO of Logic Fruit Technologies, brings deep technical knowledge and a clear vision that have shaped Logic Fruit’s evolution from a service-focused firm into a product-driven player. In this interaction with Machine Maker, he shares the company’s SBC development strategy, its collaborative engineering model, and how India is taking confident steps toward embedded technology leadership.

Single-board computers (SBCs) have long served as essential platforms for embedded computing in sectors ranging from education to defense. In India, Raspberry Pi and BeagleBoard have become mainstays for prototyping. Yet when it comes to rugged, mission-critical applications, especially in aerospace and defense, sourcing has traditionally leaned on foreign-made industrial-grade boards. That gap is beginning to close.

Logic Fruit Technologies, a key engineering services provider for high-speed data interfaces, has begun to change this equation. In collaboration with DRDO and other partners, the company is actively building indigenously designed SBCs that meet military-grade specifications, developed, tested, and assembled within India.

Strategic Shift Toward Product Development

Sanjeev Kumar, highlights, “Our strength has been high-speed interface design, PCIe, ARINC 818, 10G Ethernet. That continues. But increasingly, we are transitioning toward building full-fledged computing platforms with end-use in defense systems and aerospace,”.

The company’s flagship SBC, the Kritin iXD 6U VPX-SBC-1700, is engineered on the VPX form factor and powered by the Intel Xeon Ice Lake D-1700 series. Designed to withstand high-performance demands and extreme environments, the board integrates a 10-core Xeon D processor and 64 GB of DDR4 RAM. “It’s one of the most complex designs we have undertaken. A 20-layer PCB with 36 DDR4 components, co-designed with Intel to ensure signal integrity and power efficiency,” Mr Sanjeev added.

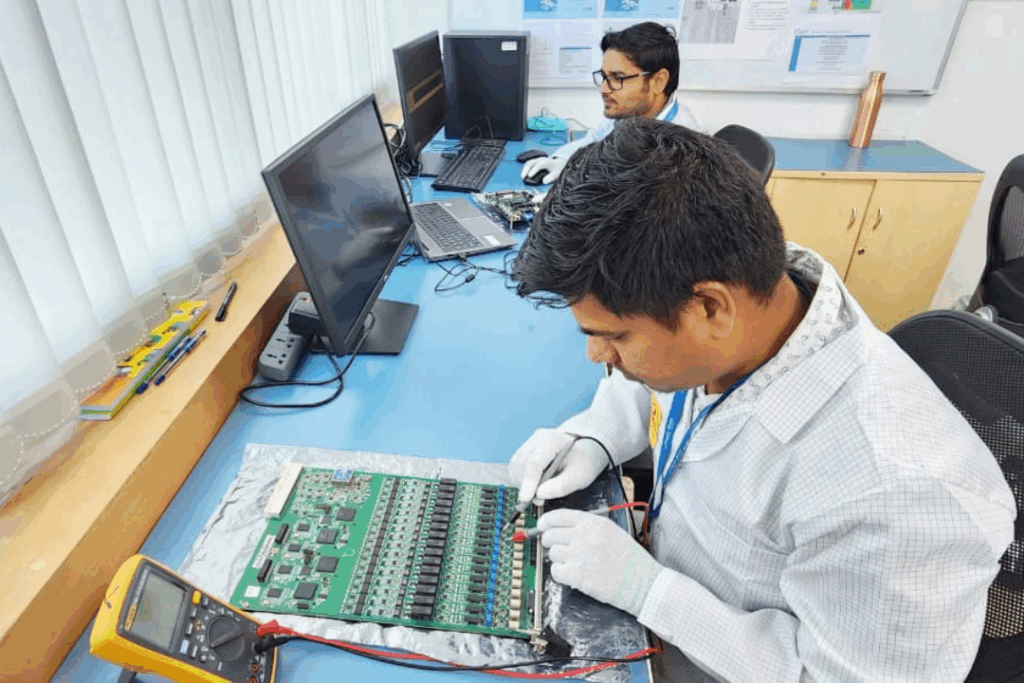

Design Rigor with Local Execution

While PCB fabrication still occurs in the U.S. due to its manufacturing complexity, the board assembly is handled in Bengaluru via Indian EMS partners. Everything else, from BIOS development to OS porting, is executed in-house. “We have consciously avoided any sourcing from Chinese vendors. Components are either U.S.-origin or from trusted international suppliers. Even if silicon fabrication happens in Taiwan, the bill of materials is curated to meet national security standards,” Mr Kumar clarified.

India currently lacks domestic silicon fabs for processors and memory, but with new projects underway in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, Kumar believes the supply chain will evolve to support full-stack electronics development in the next few years.

Built for Mission-Critical Applications

Beyond its processing power, the Kritin iXD board includes an AMD FPGA SoC for system-level customization. “We use the FPGA SoC to introduce functions like sensor data fusion and high-speed imaging. This allows flexibility to tailor systems for infrared surveillance, radar processing, or autonomous flight,” said Mr Sanjeev.

Additional designs are in the pipeline, including a board that integrates AMD’s Versal SoC alongside x86 processors, allowing for tighter integration between programmable logic and general-purpose computing.

Patents, IP Licensing and the Shift to Silicon

Logic Fruit is not only building hardware. The firm holds a joint patent with DRDO for ARINC 818-based video processing IP and has licensed it to international defense firms. Work is underway to convert its soft IPs into silicon-ready IP blocks compatible with upcoming Indian SoCs. “Licensing is a natural extension of our design work. We are not trying to become a fabless semiconductor company, but we want our IP to be silicon-compatible so Indian chipmakers can integrate them easily,” Mr Kumar said.

Mr Kumar sees competition in the SBC space as collaborative rather than adversarial. While companies like VVDN Technologies, Incore Semiconductors, and Mindgrove Technologies are developing their own solutions, Logic Fruit is carving out a distinct role. VVDN, for example, is focused on AI platforms for edge applications, whereas Logic Fruit’s SBCs are built for harsh environments and military-grade use. Even with some technical overlap, the use-cases remain clearly different.

Mindgrove’s Secure-IoT chip, for instance, targets low-power applications, while Logic Fruit focuses on high-throughput systems. Yet Kumar acknowledges the opportunity in working with RISC-V-based cores from Incore. “There’s merit in combining a RISC core with a high-performance SoC. That’s something we are actively evaluating, and we expect to unveil a development roadmap for a complex SoC within the next quarter,” he said.

While defense remains the anchor, Logic Fruit has plans to extend its platforms into industrial automation, automotive systems and robotics. Conversations are already underway with UAV manufacturers, IoT start-ups, and system integrators. Mr Sanjeev mentioned that once Logic Fruit’s SBCs mature in aerospace applications, their adaptation into other industries will follow naturally, as the design headroom allows for such flexibility.

Looking Ahead

Logic Fruit’s transition from service-led projects to product-based solutions represents a shift in how Indian companies are approaching electronics manufacturing. With a firm footing in high-speed IP, a growing hardware portfolio, and a partnership-oriented mindset, Logic Fruit is contributing to India’s ambition of technological self-reliance. “The hardest part isn’t engineering, it’s knowing what to build,” Mr Kumar said. “Now, through real collaboration with DRDO and our industry partners, that clarity is beginning to emerge.”

As India continues to strengthen its semiconductor and electronics ecosystem, efforts like these are setting a clear direction, where the country does not just assemble, but engineers the very backbone of future technologies.